“Shield’s Man’s Invention saved WW2 Merchant Seamen“

In a national newspaper in April 1943 was an article about life saving Equipment being produced by the factory of Robert Stanley Chipchase who was the Chairman & Managing Director of Tyne Dock Engineering Co. LTD. in South Shields. He was born in South Shields in 1886 son of James William & Sarah Jane Chipchase, although it seems his parents divorced in 1897. In 1918, after serving as an officer in the Royal Engineers during WW1, Robert married Margarita J. Reed in 1918 and in 1919 son Kenneth Reed Chipchase was born. The family lived at 190 Sunderland Road.

As the reporter walked into the assembly area with Mr. Chipchase she noticed that the female workers didn’t even pause or look up, so intent were they to concentrate on their work. These dedicated workers were making life saving rafts for ships.

Mr. Chipchase told the visiting journalist

“You see they are saving lives – that is what gives them the energy and the will. Most of these women have husbands or sons at sea and some have lost family members in the navy or merchant marine.”

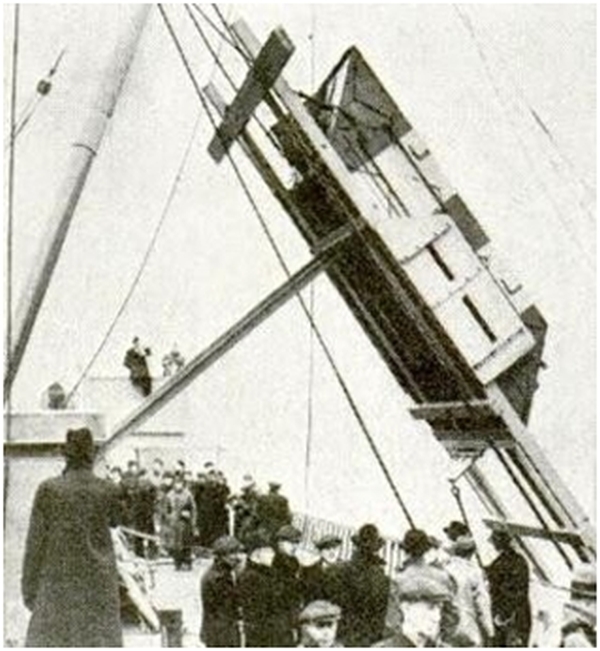

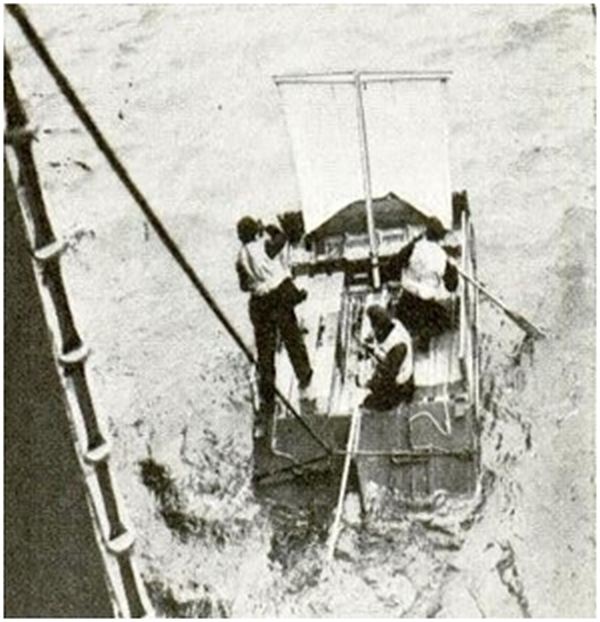

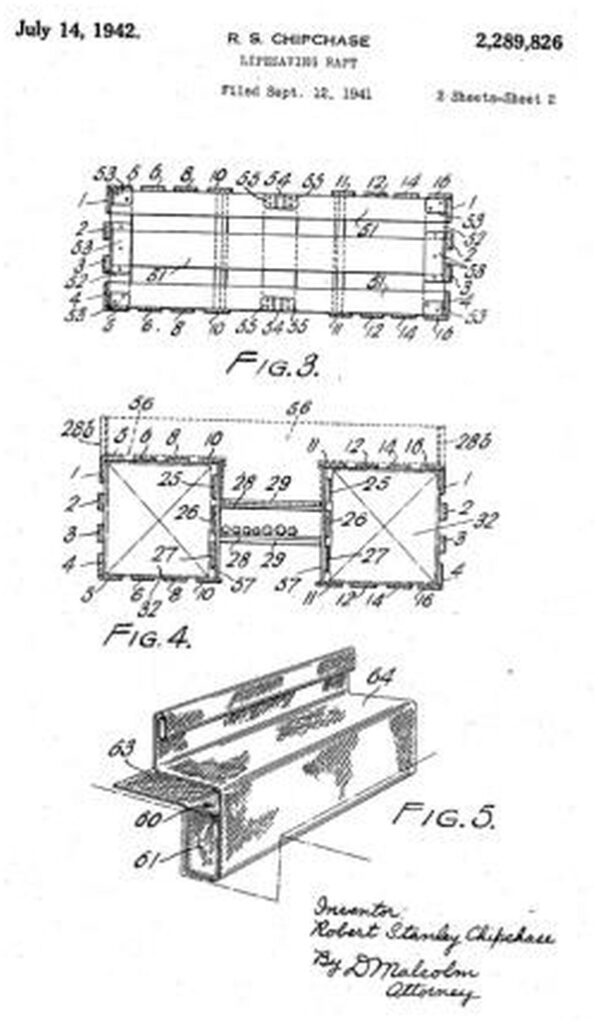

Robert Chipchase invented this raft in his spare time. He had completed a model of it just before war broke out. Unusually it had a method of launching that required no more than the kick of a boot and no matter which way it hit the water was afloat.

He had worked so hard on the raft because he was certain that Germany would use U-Boats like they did in the last war, and he wanted Britain’s seamen to have the best means for their protection for the peace of mind of their families back at home. He sent his finished design to the Government which they seized with enthusiasm.

It was sent to America, but there was a legal problem with the patent as there were uncertainties as to whether it could be copied. Robert did a very noble thing and surrendered all his patent rights and profit on the design. He said

“I couldn’t make money out of people’s lives.”

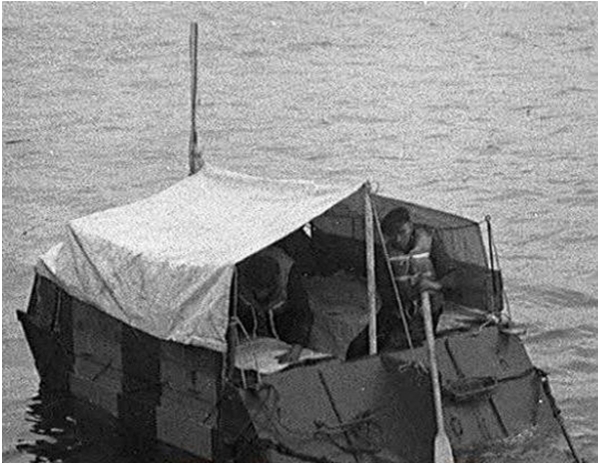

The Chipchase Rafts were made in two sizes for the different size Merchant Ships. The larger one was over 13ft by 6ft and was fitted with bulletproof buoyancy tanks filled with Kapok. There was storage for water, medicine, rations, ropes and an 8ft mast. They were made of wood and painted grey.

Mr. Chipchase was never happier when South Shields men visited the premises to tell him that his raft had saved their lives. In fact he made a point of talking to survivors to find out ways the raft could be improved through practical experience. By doing this he discovered that the worst thing suffered by shipwrecked seamen was their legs swelling from frost bite and salt water. He came up with a very simple solution – a long canvas bag that 6 men could sit in, peg at the top to keep the water out and gain warmth from each other. Then he found out that the Germans machine-gunned men inside the rafts and the bullets often pierced the one water tank, so he increased the number of tanks. Robert was told that during low level attacks on ships, the man defending the ship on the guns was the main initial target for German planes and when killed the ship was usually sunk. So, he designed protection for the gunner which moved in any position for optimum security.

Robert Chipchase told the correspondent

“Nothing’s too good for seamen, nothing I can think of – the thanks of men, not money, that’s all I want”

When the journalist arrived in South Shields on walking around the town she observed “practically every family is connected with the sea through a son or a husband. As I walked through the tightly-packed cobbled terraces there was always some house with the curtains drawn across in mourning. The Chapel at the back of the Mission has no space left for the brass plaques that commemorate the men who have been sunk by enemy action.”

She described the South Shields seamen she spoke to as

“men of understatement, because all their lives they have been fighting – gales, icebergs, typhoons. Added to this list are U-Boats and enemy aircraft.”

She also read some of the letters these men had sent to shipping offices:

I beg to inform you that I had a very exciting trip, and would not have missed it for the world. Everything aboard is OK except for the loss of an anchor and chain.

But then the journalist found a different story when she looked at the Ship’s Log of that journey to South Africa and found a precise statement detailing twenty- four hours of attacks by torpedoes and Messerschmitts which concluded:

The final torpedo crossed our bows closely, but we could not follow its wake in the gathering dusk.

The same newspaper ran a story on the 19th April 1943 about Albert Edward Wallis a 46 year old tough Atlantic sailor of Vine St South Shields, who on his return from a voyage had crept into his home in the early hours of the morning to lay a toy gun beside his sleeping son Raymond.

Weeks before Albert thought he’d never see his little boy again when his ship was hit by torpedo and they were forced to abandon ship. He had bought the gun in New York and for some reason had kept it in his pocket. When he was heaved into the rescue ship he discovered the toy still in his pocket which was the only thing he managed to save. It was the 6th time he’d been torpedoed.

Despite all the dangers involved there were queues of Tyneside men at the shipping offices wanting to do their bit. Very young boys like 16 year old Robert Wood who in 1943 had already completed two voyages. He had endured one bad one with gales and U-Boat attacks.

In 1941 when a British ship was caught in an Arctic blizzard and tried to send out an SOS it discovered that ice had broken the radio aerial. Ernest Richardson who was 20 of Akeman Way, South Shields volunteered to replace it. He climbed the mast in blinding snow with his gloves off. It took him 40 minutes to replace the aerial and his hands froze to the mast. Another Shields man Able- Seaman Marshal Mordew of Wawn St grabbed a rope and went up the mast to rescue him. He put a rope around Ernest and slid down to the deck then lowered the wounded young man down. Ernest lost three fingers to frostbite but he saved the ship. He was landed in Iceland 11 days later to be treated in hospital. He was later awarded the British Empire Medal.

The Newcastle Journal of the 21st March 1944 featured a story about Robert’s son Kenneth – Surgeon Lieutenant Kenneth Chipchase of Sunderland Rd. South Shields who was serving on the Sloop HMS Magpie protecting shipping convoys. The day before there had been headlines in the papers ‘6 U-Boats Sunk in Greatest Patrol of War!’ The Magpie, which Kenneth was serving on had taken part in this action. When the little ships came into port in Liverpool, the First Sea Lord was among the huge crowd to cheer them in. He described the action undertaken by HMS Starling, Wild Goose, Woodpecker, Kite and Magpie as a Battle of Trafalgar in miniature with the Nelson touch applied and perhaps one of the greatest cruise undertaken in the war by an escort group. Two convoys of ships had been successfully guarded on their journey in the Atlantic and not a single merchant ship lost. Day and night everyone on board the sloops had manned the guns and depth charges, thrashing the enemy wolf packs and saving the valuable convoy.

Surgeon Lieutenant Kenneth Chipchase, only 24 was singled out for praise because he successfully carried out a major operation at sea. One of the other vessels signalled to the Magpie that an emergency operation had to be carried out on one of the men so Kenneth was transferred to the other ship. He carried out the operation successfully despite the heavy rolling of the ship. Dr Chipchase practised in South Shields until his death in 1974. HMS Magpie also served as an escort during the D-Day landings.

These Merchant seamen kept the country supplied with raw materials, arms, ammunition, fuel, food and enabled the country to defend itself. They were aged from 14 to the late 70’s.

36,749 were killed. 5,720 taken prisoner, 4,707 were wounded, totaling 47,176 casualties. The war could not have been won without them. Who knows how much higher the death rate would have been had it not been for Robert Chipchase’s invention.

Written and researched by Dorothy Ramser